By Rick James, Principal Consultant at INTRAC.

Founder leaders are not normal people. They are extra-ordinary human beings. As social entrepreneurs, they have created something meaningful and successful where nothing previously existed. The NGOs owe their very existence to the founder.

Leaving an organisation is painful, especially if you have created it. Not surprisingly, leaders shy from the emotional cost of leaving. “What do you mean I’m no longer good enough?” they ask. Even when it goes really well, transition is tough – it involves anxiety, fear, grief, anger, and frustration. Emotions are intensified during times of uncertainty and change. Emotions can take a long time (if ever) to adjust. Leadership transition is too significant to be anything but bumpy, especially with founders.

Some founders liken moving on to giving your baby up for adoption. This is much worse than your child growing up and leaving home.

Some founders liken moving on to giving your baby up for adoption. This is much worse than your child growing up and leaving home.

Few parents would trust anyone else to look after their child with the same love and commitment than they have. So it is not surprising that founders find it hard to trust handing their organisation on.

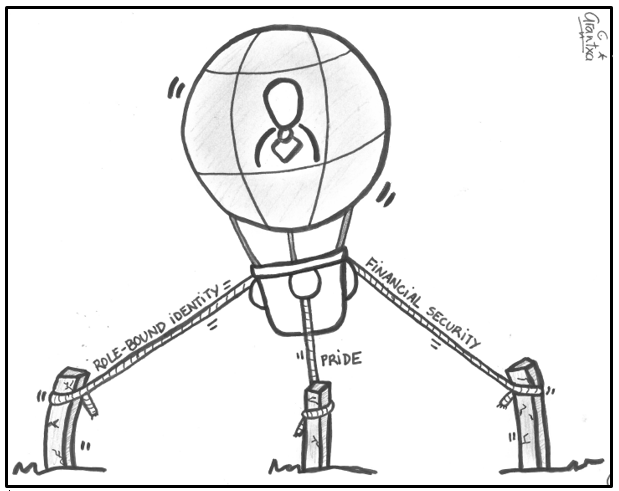

Few founders can let go without help. They need challenge, encouragement and support along the way. Three common blockages often make transition difficult:

Role-bound identity Ensnaring pride Financial security

Role-bound identity

For many founders, their leadership has become inextricably intertwined with their identity – their sense of who they are. Many no longer can fundamentally differentiate themselves from the organisations they lead or created. Their role as leader is a major part of who they have become. So they find it hard to countenance a meaningful life without their position.

Their sense of self, their identity, has become confused with their job in the organisation. They have become blind and unable to distinguish between what is for the organisation’s benefit and what is for their own. We all need outsiders to help with our blind spots. This is a key role of the board.

Founders invest considerable time and emotional energy in making their dream a reality. The demands this places on leaders tends to narrow their outside community interests. They may have reached the stage of life where children are leaving home. This may mean that just when they should be letting go, they are clinging tighter to their job for their sense of meaning and purpose.

Ensnaring pride

We all tend to overestimate our own importance. Founders in particular tend to feel indispensable. They may have been told this frequently over the years by loyal staff and supporters. The reality is that we are all probably a bit less vital than we think. If anyone is truly indispensable, then there is a real problem in the organisation. It may be better to find this out sooner rather than later.

Founder leaders often think of legacy. It may be a useful way in to discussions about moving on. But sometimes focusing on legacy can have the opposite effect. Founders are so frightened of putting their legacy at risk that they hold on even more tightly – undermining the very thing they wish to preserve.

Financial insecurity

If you are a commercial entrepreneur you can sell your successful business and walk off into the sunset with the big payoff. There is a powerful financial incentive to let go and move on. Social entrepreneurs have no such financial incentive. If anything the reverse. You are in reality likely to be worse off. At such an age, you may not be able to walk easily into another job. Leaving employment may have serious financial consequences as they have built up on-going financial commitments (mortgages, university fees).

Surfacing the real issues

For many, these three blockages to letting go hide below the surface, in the sub-conscious. They are rarely acknowledged and even more rarely openly discussed. Their invisibility only adds to their power. To help leaders let go we may need to surface and explore these restraining forces. They will be different for different people. It may be worth asking questions about “Am I still the leader this agency needs?” (Tim Wolfred, p 15 , 2008, Building Leaderful Organizations: Succession Planning for Non-Profits, Annie Casey Foundation).

But perhaps more importantly, it’s also about reinforcing the positive motive for change as we shall see in the next blog.

Illustration by Arantxa Mandiola Lopez. CC BY 4.0.