By Vera Scholz.

It’s unmistakably the year of sustainability. Last month, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have quietly – perhaps too quietly – replaced the Millennium Development Goals with a new and ever longer list of targets. What is more, shortly, government and civil society delegates from all over the world will make their way to Paris to negotiate a new global agreement to curb accelerating climate change. As new goals and targets require robust monitoring and measurement, the United Nations has proclaimed 2015 the Year of International Evaluation, with the final event taking place in Kathmandu, Nepal this month. However, beyond this obvious link, what implications does the beginning SDGs era really have for all those professionals out there who, like me, consider themselves “development monitoring and evaluation practitioners”?

Two weeks ago, an assembly of evaluators and evaluation stakeholders in Bangkok – organised by the International Development Evaluation Association (IDEAS) – attempted to provide some direction as to what the role of evaluators might be, looking ahead. Keynote speakers and discussants referred to a whole list of considerations. For me, the most interesting were:

- The need to move from evaluating and learning about the ‘now and here’ to the ‘then and there’, taking the longer-term view of what an intervention is really achieving and what we should learn from it. This means expanding the outlook of evaluation to the (likely) ecological and social long-term sustainability of development interventions.

- Ways of using evaluation to nurture risk and innovation instead of risk aversion and business as usual.

- The necessity for evaluators to leave the technical expert realm and become activists in their own right.

- Embracing working with those growing subsets of the private sector genuinely interested in social impact and its measurement, thinking outside the boundaries of our own comfortable Official Development Assistance sphere. We are not talking about establishing the effects of Corporate Social Accountability but of core economic activity that arguably has much greater potential for social transformation than ‘International Development’ measures.

Easier said than done. It was not the first time I had heard these ideas and I could not help but wonder why we were not also spelling out the numerous barriers to realising evaluation that is taking a longer-term view and driving innovation. These obstacles are by no means new and need to be addressed. I will mention those again that strike me as the most crucial ones.

Easier said than done. It was not the first time I had heard these ideas and I could not help but wonder why we were not also spelling out the numerous barriers to realising evaluation that is taking a longer-term view and driving innovation. These obstacles are by no means new and need to be addressed. I will mention those again that strike me as the most crucial ones.

Lack of resources to conduct long-term impact assessment.

How would we take the long-term view as internal or external evaluators if there is usually little funding available to return to interventions long after they have finished? Are we right in our assumption that currently all parties involved are genuinely interested in the results (or lack of results) that routine long-term impact assessment might uncover? I suspect not and I would have welcomed a conversation about this at the conference.

Too many disincentives for honest learning about failure.

This links closely to the first barrier mentioned. What would evaluations that “nurture risk and innovation” look like? While failing forward is celebrated openly by many organisations, rarely does one come across a donor-funded organisation that is completely comfortable in discussing and understanding its failures – for understandable reasons. The same conundrum likely applies to institutional donors – remember the not very enthusiastic 2014 ICAI review of how DfID learns.

I would have liked to hear more about what big funders like the Asian Development Bank and national governments are doing to reshuffle existing incentives for evaluators and evaluands to engage in honest learning. And while everyone on the podium agreed that accountability and learning are not mutually exclusive at all, are there examples out there of organisations being truly accountable for learning and improving? If so, how are they doing it?

We prioritise technical rigour of evaluations over the process of stakeholder engagement.

In a world where choosing the right evaluation methodology and tools is still generally valued more than engaging with the right stakeholders early on in the process, how can professional evaluators embrace their values-driven, “activist” selves without appearing to compromise standards of rigour and accuracy? The two sides of this debate were well represented at the Bangkok event – there were those evaluators defining their job as the delivery of high quality, rigorous findings and those few explicitly seeking to have an impact on their client’s work but also results.

This discussion will likely be gaining momentum by the ongoing exploration of whether and how to professionalise the evaluation sector, another debate well summarised by the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group’s Caroline Heider. I personally feel evaluations have a duty to consider in explicit terms how to maximise their usefulness and uptake, which in turn has implications for how they are commissioned as well.

A lot of tricky issues and questions, and we surely haven’t got our heads around these. There is still hope (and the need) for the final event of the International Year of Evaluation to be addressing some of these.

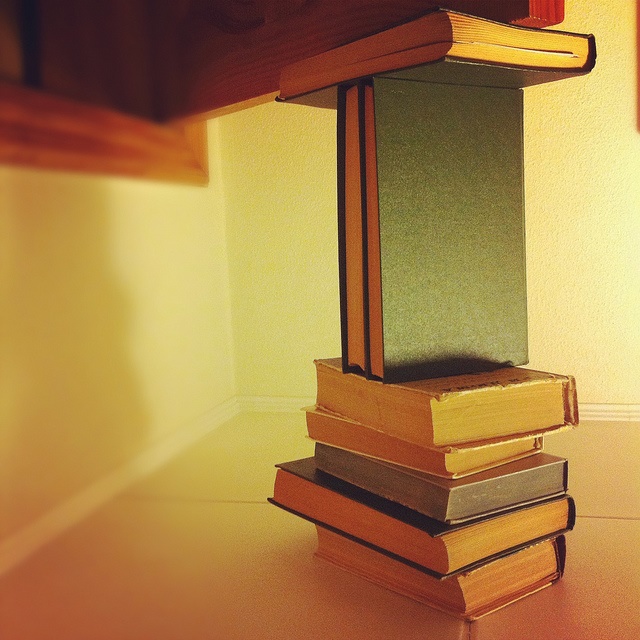

Image credit: “Support” by Igor Grushevskiy. Via Flickr – CC by 2.0.