By Rod MacLeod

How to prove resilience? For disaster risk reduction projects, the only sure way is to see what happens when an actual disaster strikes.

Before that, you can check whether a community has produced a vulnerability assessment, mapped the village, developed a plan, improved physical infrastructure or trained rescue teams. But it is only when another cyclone hits coastal communities that the effectiveness of these measures can be gauged. Did the warnings arrive in time? Did people get to the cyclone shelter and was it adequate?

In this sense, COVID-19 provides not only huge challenges, but also an unusual opportunity. Civil society organisations (CSOs) and the entire eco-system that supports them are being tested by the pandemic as never before. As I wrote in April, what began as a health crisis, has now also become a full-scale economic crisis.

The financial challenge

Financing has been the most pressing immediate concern for many organisations, particularly those starting the crisis with low reserves. Lockdowns have meant that CSOs in the South have had to stop, curtail or adapt activities. This has jeopardised the grants on which many CSOs depend, as they are often linked to activity plans. While the work of a CSO is interrupted, its costs – such as salaries and rent – continue. The evidence is that many donors have listened to the CSOs they support (in line with INTRAC’s advice early on in the crisis), and have tried to show flexibility. This has taken the form of extending funding periods, loosening requirements and providing emergency support.

The financial position of INGOs hinges on their mix of income sources. Some governmental donors have curbed budgets. This is the case with the UK, where the 0.7% of GDP commitment to aid operates in real time, leading to rapid reductions – including funding for civil society. Other donors are holding firm for now, but CSOs are concerned that they will cut back in future years, in the face of the pressure to rein in massive national deficits. Individual donors, faced with loss of income and greater personal risks, have reduced their charitable giving. Similarly, some CSOs have found that corporates have been reluctant to make additional commitments, although foundations living off endowments seem to have held up better. Ironically, INGOs that had sensibly diversified their income base through charity shops (e.g. Oxfam), hotels (e.g. YMCA), events (e.g. War Child) or English lessons (e.g. the British Council), have seen reducing incomes due to the discriminatory impact of COVID-19. This is just unlucky, rather than bad planning.

The management challenge

Adaptive management – which can be understood as ‘constant data collection and analysis in order to adapt and refine programmes on an ongoing basis’ – has been much in vogue in recent years. Current circumstances underline its importance for CSOs as never before. Existing strategic and annual work plans have rapidly become irrelevant with this new threat. The most responsive organisations have launched into major processes of modelling future scenarios with revised budgets, determining how project work can continue and taking hard choices on staffing (furlough, salary freezes, moving staff to part time and redundancies). This has tested CEOs, the Senior Management Teams and Boards to the limit. Having to work remotely has added an extra dimension of complexity. In making difficult choices, it has also been vital to bring along the broader body of staff and volunteers and maintain morale, which includes addressing well-being issues. At the same time, CSOs are having to think through whether and how they need to change their programmatic approach in the short and longer terms in response to COVID-19.

Planning is everything, the plan is nothing.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

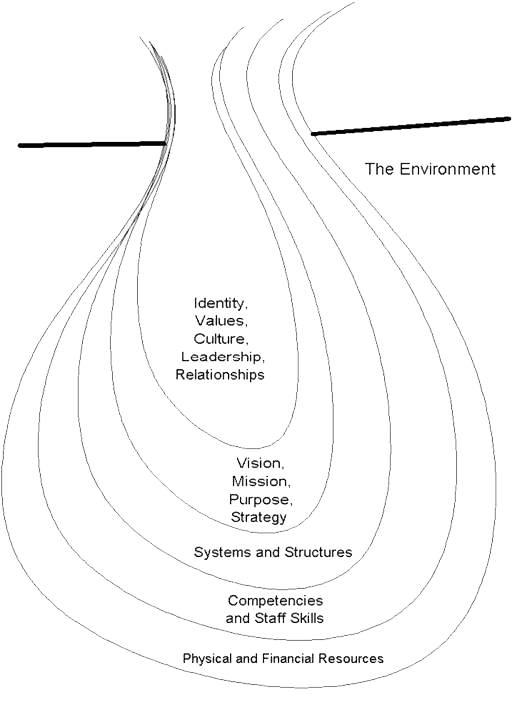

The heart of the onion

Resilience is not just a technical problem. It cuts to the ‘heart of the onion’ – the vision, mission and motivation that define an organisation. Making rapid and drastic adjustments has clearly been easier where all the stakeholders share a passionate commitment to what a CSO is trying to achieve. It is a combination of the people, their attitudes, interactions and actions that define an organisational culture and enable it to work through hard times.

Conclusions on organisational resilience

COVID-19 is not yet over, and some predict that the pandemic’s effects may linger for many years to come. CSOs with a good survival plan for 2020 may struggle into 2021 and beyond.

However, the early indications are that the CSOs which have proved most resilient to the shock of COVID-19 so far – both in the Global South and the North – have benefited from a combination of a good starting position, supportive donors, effective management and a strong commitment to their core values – as well as a dose of luck. While many organisations are struggling today, those that survive may be the stronger for it tomorrow.

The key lesson is that work on organisational resilience is not something that can be seen as an unaffordable luxury in the future. This must be seen as a priority for CSOs themselves, their funders and CS support organisations like INTRAC.