By Rod MacLeod

This blog is part of INTRAC’s season on shifting the power through organisational development. The season is part of our celebrations of INTRAC’s 30th anniversary.

I was shocked and disappointed. Sitting in a rural Ugandan sub-county planning meeting a few years ago, an INGO staff member informed the gathering: “we will be using the latest technology… it is called a logframe and will produce a strong plan for your area”.

I disagreed with what he said on many levels. Firstly, the logframe is a tool and will produce nothing by itself. Secondly, the logframe is not the “latest technology”. It has been around for several decades and has attracted many criticisms. Thirdly, and most importantly, introducing a planning process by highlighting a single tool detracts from what is most important: engaging local people in discussing issues affecting their communities in a participatory and comprehensible fashion.

This event epitomises many of the inherent problems of seeing tools as ‘the answer’. It also shows how donor-designed tools often do nothing to shift the power; if anything, they do the opposite. Sadly, I’ve experienced variations of this same incident throughout my 30 years in development.

The popularity of tools

At INTRAC, we are often asked by clients to give them “the latest tools”. Whether for assessment, planning or evaluation, many feel this is part of what a proper consultant should bring with them. I’m frequently asked: “which is the best tool?”. It is as if the act of identifying the right tool will automatically unlock tricky problems and lead to the best solution.

Tools have a strong appeal in our sector for a number of reasons. Social change, such as reducing poverty or promoting gender equality, is highly complex and uncertain. Problems have multiple causes and there are numerous actors exerting positive or negative influences within a rapidly changing ecosystem. There are so many possible interventions to choose between. Assessing and attributing outcomes and impact in an objectively provable sense can be extremely difficult. In such complex situations, it is not surprising then that we reach out for tools that will provide a sense of control.

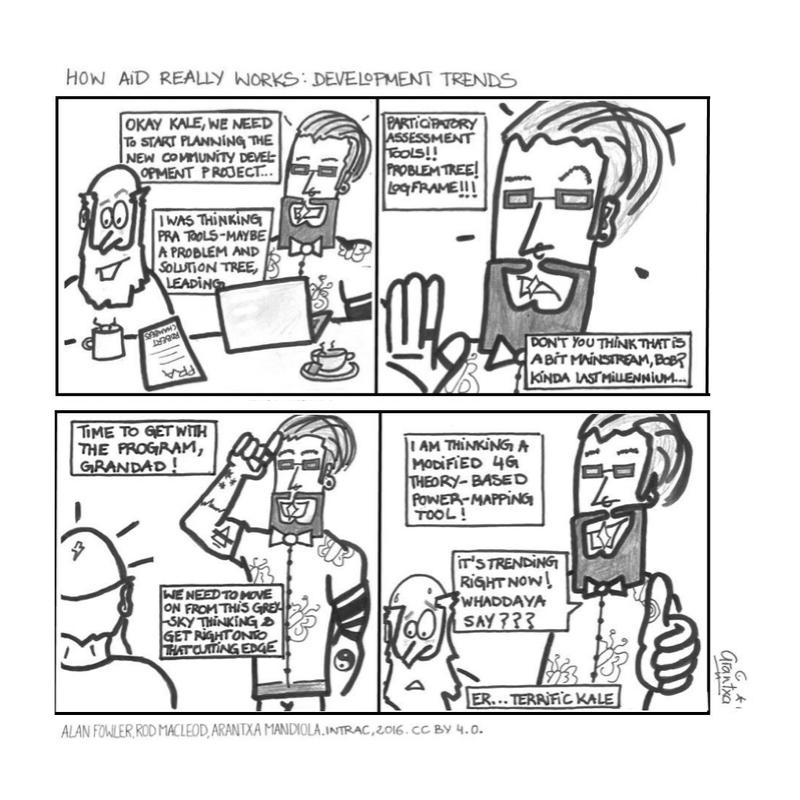

The idea of finding innovative, or the most modern tools is even more seductive. There is no better way to prove your fashion credentials in the social development sector than by flaunting a shiny, new, and previously unknown tool. Such tools are then compared to “traditional”, and implicitly inferior, ways of doing things. Knowing the latest tool enhances the status and power of the one who wields it.

What is wrong with all this? If tools help us do the job, why not use them, and ensure that we have the latest version?

The downside of tools

Tools can often concentrate power. They are usually designed by those with power over the resources. If tools are complex and require sophisticated analysis, they tend to be applied by “experts”. This gives the tool operator power over others. So, many tools are really what we might call “power tools”. They often undermine the participation that we know is so vital if we are to genuinely shift the power. My INTRAC colleague, Rick James, is fond of saying to Northern agencies: “never inflict a tool on a partner that you do not use in your own organisation”.

A tool is only as good as the person using it. Just as the best chisels in the wrong hands will not produce Michelangelo’s David, poorly used tools will not lead to good results. For example, even some of the best participatory rural appraisal (PRA) tools that intend to make sure that “people, especially poorer people, are enabled to take more control over their lives” (Robert Chambers), have at times been misused. They have sometimes been employed to legitimise a choice of programme activities which has actually been decided ahead of time. In such cases, the tools have given an illusion of empowerment, while in fact reinforcing marginalisation.

Tools can distract from what is most important. For example, donors are currently fond of using organisational capacity assessment tools with partners to ‘measure’ progress on scales of organisational strength. But in many cases, concentrating on improving scores diverts attention from a more important and fruitful discussion on the big issues underlying an organisation. Sometimes tools can be a convenient displacement activity from what is really needed.

Conclusion

Tools can be useful provided they are not allowed to occupy centre stage. They can generate and summarise information, perceptions, and opinions. But what matters most comes next. Tools do not in and of themselves produce definitive answers on how to proceed. This happens when the outputs from tools are interpreted, contextualised, analysed, and acted upon. This is the most crucial part and is best done through the age-old process of reasoning collaboratively: reviewing the evidence, weighing the arguments, and making considered judgements.

Tools need to be recognised for what they are – simply ways of arranging interactions and gathering data. They have no magical power. When they are helpful, we need to handle tools with care. We need to manage the tools, rather than let the tools manage us. And sometimes, a tool is not needed at all.

Rod MacLeod joined INTRAC in March 2007 as programmes director and became a principal consultant in 2011. Previously he worked with Concern Worldwide in Cambodia, India, Sudan and Haiti, in a range of management positions including three at Country Director level. He has also worked at Y Care International as Director of Programmes and also as International Programmes Director for Progressio (formerly the Catholic Institute for International Relations), both based in London. Other roles have been at Save the Children Norway as an adviser covering East Africa and the Horn of Africa, and he has also worked as a freelance consultant based in Uganda.